Model G hydraulic pressure.

Printed From: Unofficial Allis

Category: Allis Chalmers

Forum Name: Farm Equipment

Forum Description: everything about Allis-Chalmers farm equipment

URL: https://www.allischalmers.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=110500

Printed Date: 20 Dec 2025 at 8:27pm

Software Version: Web Wiz Forums 11.10 - http://www.webwizforums.com

Topic: Model G hydraulic pressure.

Posted By: PJHoward

Subject: Model G hydraulic pressure.

Date Posted: 16 Aug 2015 at 1:57pm

|

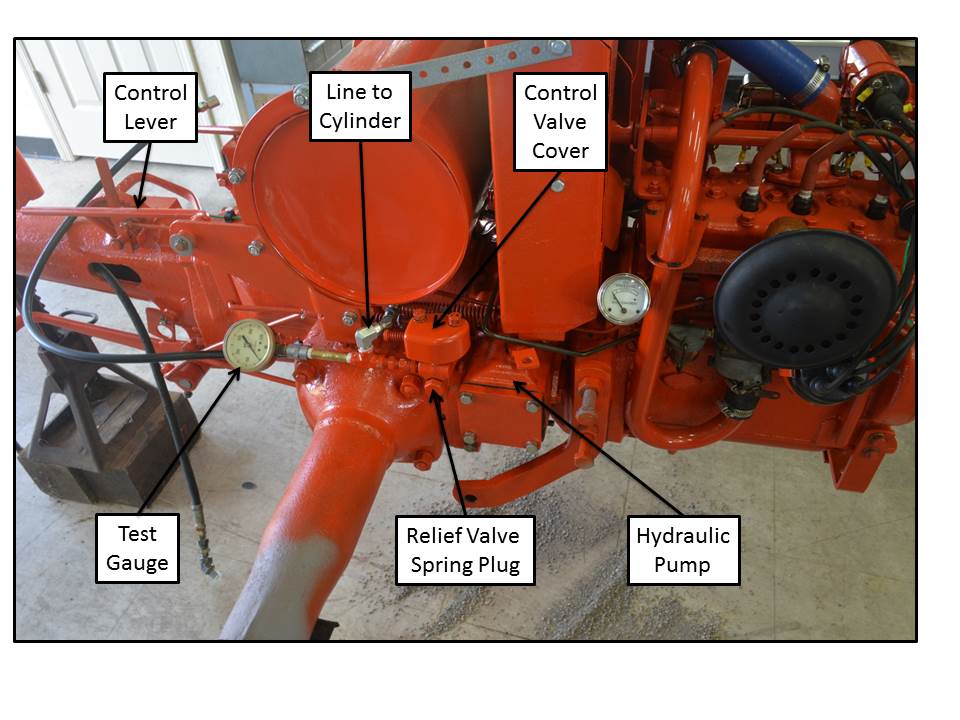

I had one

that threw me for a loop this week. I have been rebuilding a 1949 AC Model G. The

cleanup was going fine until I got around to connecting up the hydraulics. The

Model G has front and rear cylinders for lifting equipment. The rear cylinder

has a spring return and a needle valve to adjust the timing between the two. The

operator can adjust the needle valve to delay the lifting of the rear

cultivator at the row end so the front would be out of the ground when the rear

finishes the row. After I cleaned and reassembled the pump, I remounted it and connected the rear cylinder to test the system. I started the tractor and the hydraulic cylinder wouldn’t move. It had a problem: the system would only reach about 100 PSIG. The pump bypass relief valve consists of a spring that pushes on a ball bearing that seals the pump output from the return sump. When the system pressure exceeds about 900 PSIG, the valve opens and bypasses the fluid to the sump to keep the system from over pressurizing. I made new valve parts because it seemed like the relief valve was opening too soon and not allowing the pump pressure to reach the required 900 PSIG. After the 5th or 6th pump removal, I decided to replace the spring and ball with a machined rod that would seal the bypass to determine what the ultimate pump pressure would be. I was astonished to find the pump only produced the same 100 PSIG. That drove me nuts until I happened to spy the problem: the G has a latch on the clutch pedal to keep the clutch plates from sticking together during periods of inactivity. I haven’t adjusted the clutch yet because the tractor is on stands. I hooked the clutch rod up and set the adjustment midpoint and assumed I would adjust it when it came time to mount the wheels. As luck would have it, the clutch was just barely engaged when the latch was used. The amount of engagement was just enough to reach 100 PSIG before slipping. Had I turned the clutch nut 1 turn more or less, the problem would have been obvious from the start.

|

Replies:

Posted By: Bill Long

Date Posted: 16 Aug 2015 at 4:27pm

|

A very excellent post. All items are fully explained. Funny, how some of the easiest thing are sometimes overlooked. I still remember a customer had hydraulic problems on a C. Drove a total of 40 plus miles to engage the pto. Great job on the G! Looking good. Better than new Good Luck! Bill Long |

Posted By: CTuckerNWIL

Date Posted: 16 Aug 2015 at 7:23pm

Bill, it must have been easier to drive 40 miles than to read the operators manual.

------------- http://www.ae-ta.com" rel="nofollow - http://www.ae-ta.com Lena 1935 WC12xxx, Willie 1951 CA6xx Dad bought new, 1954WD45 PS, 1960 D17 NF |